A little more than a year ago we began collecting hand written stories from Venezuelans as they fled into Colombia for refuge and work. We left ledger books with numbered pages in the places they slept at night — these in private houses opened by good hearted Colombians and in more formal places called ‘refugios’ operated by national and international NGOs. As of February 2020 it was estimated that their numbers had grown to almost two million. As the importance of catching their story and this moment in history touched us, we formed ourselves into a literary advocacy NGO called TodoSomos. With the declaration of the global pandemic of COVID19 and cases appearing in Colombia, the Venezuelan-Colombian border was closed March 14 and this exodus from Venezuela ceased.

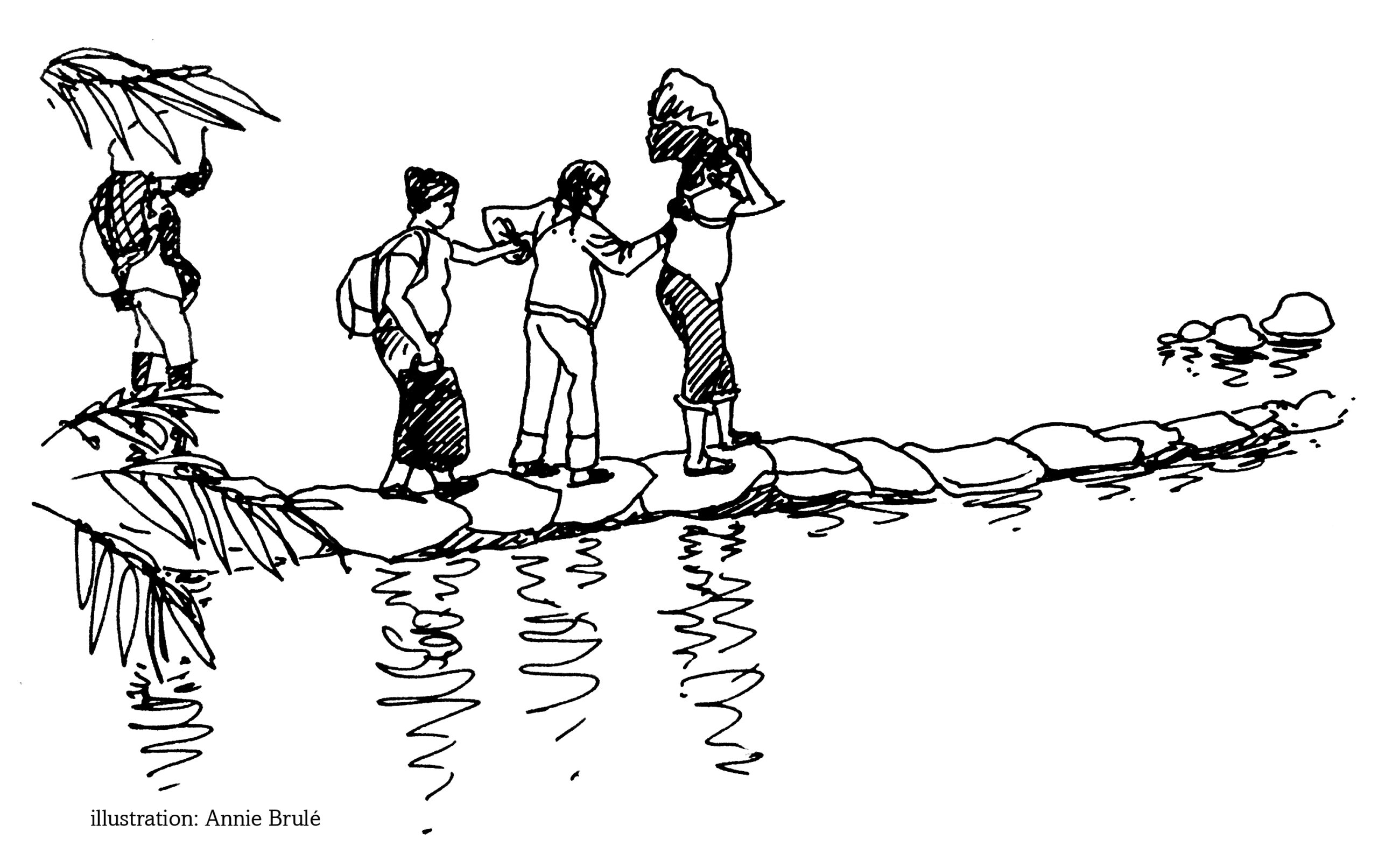

On March 23, in response to the epidemic, the Colombian government declared a state of emergency and issued a national ‘stay at home’ order. With the essential ‘closure’ of the informal work sector, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans in Columbia have found themselves out of work, out of money and at risk of losing their short term housing. By the middle of April several thousand had been evicted in urban centers. This has resulted in large numbers of Venezuelans headed to the border — bused from cities and a steady stream walking and trying to hitch rides on trucks. They come from all over Colombia — Bogota, Bucaramanga, Cali and as far as the border with Ecuador. Their destination is Cúcuta with the hope to be able to walk across the bridge into Venezuela and San Antonio. They make the choice often without other options: evicted and homeless, it’s sleeping in the plaza or a park, setting out on foot or if lucky it’s boarding a bus provided by an Alcalde (major) who wants to move the problem (refugee) from his area of responsibility. Most have heard the rumors of the poor conditions in San Antonio, and a mandatory military supervised two week confinement, little running water or food ….. and still they come. The last part of the journey is from Bucaramanga to Pamplona to Cúcuta, the first leg up and over a 12,000 foot mountain pass, the second leg is down from Pamplona to Cúcuta. By bus together these legs take four to five hours. On foot it can take up to a week.

Initially here for TodoSomos, with the pandemic of COVID19, I have been recruited to provide technical support to a consortium of agencies (UNHCR, PAHO, national and international NGOs). Most have been here since 2018 to help those fleeing Venezuela. Their challenge today is to figure how to help the thousands of Venezuelans on the Colombian side of the border and the 500 per day that are now arriving in Cúcuta trying to get back to Venezuela while the country is under a curfew similar to Colombia.

Two days ago on my return trip from Pamplona to Cúcuta I planned to stop and talk to some of the refugee groups headed to Cucuta. Approaching strangers on the road, even those walking, is awkward. I needed a greeting. As I left town, I noticed a small store open on the other side of the five way intersection. As one of the only stop lights in town flashed yellow then green I crossed and parked my bike near the entrance and took off my helmet.

It had been a little café with coffee, beer, fried food and snacks – the kind of place in normal times one would stop when waiting at the edge of town to catch your bus or to share a local piece of gossip. I felt obvious and obviously a foreigner to Colombia and to Pamplona — a tall guy with a shaved head, climbing off a large motorcycle with foreign plates. As of that day, in Pamplona (pop 55,000), there had been no confirmed cases of COVID19. As I approached, I noticed that the display cases and carts normally in the back of the café had been pushed to the front, this to prevent customers from entering. Although not 6 feet (2 meters) it did provide for a couple of feet of social distancing and ensured customers wouldn’t enter or linger. A couple sat at a table wearing masks pulled down as they talked and watched a TV blaring news of Corona virus and Colombia. I had to say something to get their attention, I suspect they would have preferred if I had just gone away.

I bought a box of ‘bocadillos,’ a traditional small sweet made from guyaba, a local fruit. There were 20, each individually wrapped in palm leaves, these all carefully packed into a thin brown cardboard box. The leaves were green and a little crisp, as if they had been in the case waiting weeks, maybe months. When I asked, ‘how much,’ he looked up an me and, when I added, ‘para todos,’ he paused and counted. It came to 4,000 Colombian pesos or about a dollar. I had a 5,000 peso note. I passed this to him and when he had change to hand me I felt myself inadvertently give him the same slightly paranoid look he had for me as I passed the bill to him. It was about ‘not touching anything touched by a stranger’ without the ability to immediately ‘wash your hands.’ It was about fear of COVID19. I put the coins in my jacket pocket, put on my helmet, climbed on my bike and avoided making eye contact with the police officer that was on the other side of the street watching me.

I rode for a bit, maybe 10, 15 minutes, looking for an approachable group. I was alone but that rarely worried me, I just wanted to make sure I found a group that was going to rest long enough that someone might be willing to write in one of our books. I passed two large groups walking and another resting, then another that looked like they were both resting and repairing one of their bags. A bit odd a hundred yards further, down the road, there was a young woman alone sitting on a rock her head and face covered by a scarf. I thought it would be a good group to try. I had done this often with groups of ‘Venezuelan caminantes’ before the Corona virus and the paranoia that has settled on society. I hoped they would talk, and maybe write.

I slowed, did a U turn and parked my bike a short distance away – they looked like a family. I shut off the motor, took off my helmet. They looked up unsure what to make of me. There were four. A thin muscular man in his late 40s; his wife a daughter in her mid teens and their son who looked 16 maybe 17. The young woman down the road a bit I was later to lean was their other daughter.

I started off, ‘Ola, soy un medico, trabajo con un grupo que ayuda caminantes ….,’ (hello, I am a doctor working with a group that is helping you all that are walking to Venezuela.)’ ‘Queremos saber de donde vienen? Cuanto tiempo tienen en el camino? Como le han tratado la policía y otro en el camino?’ (We would like to know where you have come from? How long have you been walking? How have you been treated by police and others along the road?). From a half squat, half kneeing position the father looked at me and listened. When I finished he turned his attention back to the pair of pliers, bailing wire, and suitcase and without pausing in his work he spoke, ‘…. they have treated us like untouchables, pariahs, they have pushed us from town to town; they have lied to us when they say they will help us to get to Cúcuta – they would put us on a bus on one side of the town and then stop on the other and point in the direction to keep walking. Everything was good Bogota, my children were in school, I had a good job.’ He didn’t look up, though it was clear he had finished what he had to say. His time for me was over.

They had stopped to make an extension to the frame of one of their bags, this to reinforce the pull up handle and allow them to put more bags and weight over the wheels rather than having to carry it on their backs or shoulders or arms. It was worn, one broken zipper, the wheels were small and plastic, small enough to fit into your hand. It was a cheap bag, the little axle would have been a small bolt, no bearings, no lubrication – it was a system with a short half life, a system destined for airports, light loads, not a 600 km journey on foot on rough Colombian highways carrying 80 lb.

They had taken time to find the right type of tree and the right size of branch for the brace. They needed something that would be strong and flexible but not too heavy. The ends were clean, and green, cut as if it was done at a steep angle with one clean strong stroke. I watched as they worked, each movement was deliberate, each movement had intension. They worked together, his son anticipating what he would need next – where he had to lever and hold. It was the way good surgeons work together.

I walked back to my motorcycle and pulled out the box of bocadillos and a notebook we had used in the refugios to collect hand written testimonies. Feeling a little unseemly, I handed them each a couple of bocadillos and then asked if anyone had ‘buenas letras’ (nice handwriting) and would be willing to write what he or she had had to say, would write their story. Their daughter was the only one to look up at me. I walked over to her, opened the book and turned through some pages to show her the stories others had written. As she flipped through the book, her father got up from his work, walked over, and they spoke quietly together. She then asked her mom for a pen and began to write.

The silence was palpable. I could only stand and watch as she wrote. I knew I wouldn’t or couldn’t ask for a picture. I I had been let into a sanctuary, a church and allowed to see a moment in this family that they would not choose to show others, that they only wanted behind them.

The mother and son nibbled, like one does, on the bocadillos I had passed around, it was an affirmation of sorts — at least they didn’t think I was there to poison them. I looked at what they carried, pushed and pulled. Everything was worn, soiled, plastic and seemed to be half held together with wire. There was one pack with shoulder straps, three small bags with wheels, and something resembling a pram (wheelbarrow). The bags with wheels were the type you’d see used for hand luggage in airports, the kind with the thin retractable handles. Each was loaded with multiple bags wired or strapped to these handles. The largest collection of bags was stacked onto the pram . Its single wheel no more than 10 inches in diameter. It had a small axle and a spindle that would have once held a chain.

I thought about humans and the development of the wheel and how it is what all of these walkers sought to make their burden easier – I’d seen shopping carts and wheel barrows, dozens of baby carriages, and hundreds of these pieces of airport luggage with wheels. I thought about how far this is from our lives in developed countries, where now we are annoyed we can’t dine out or move about in our cars.

It eventually came to me, the wheel of the pram…. it was the rear wheel from a child’s bike, a very small bike, the kind that would have had training wheels and a little seat. It’s the sort of thing ubiquitous in junk piles and recycling bins. They must have dug it from a bin or the side of the road along the way. It had been wired to the pointy end of two sticks a good four or feet long. These had been arranged in a sort of a long triangle, with the branches sticking out from the wide end serving as handles. By this point in the journey it would have carried a good 50 kilos (100+ lbs) for more than 500 km (300+ miles) on its little axle.

… young daughter writes..

Salimos de Bogotá la familia Figueredo Capote, incorporada por seis personas, entre ellos van 3 niños. Hemos recibido ayuda de algunas personas en cada pueblo, como también hemos sido mal tratados por muchas otras, también hemos pasado por situaciones muy feas, como: nos dejaron en pleno páramo; de noche pasamos frio y hambre, amanecierón congeladas las maletas y muchas personas que nos ofrecen llevarnos lo más cerca de Cúcuta no cumplen. Le damos las gracias a todos los que nos han ayudado en el camino.

We left Bogota, the family Figueredo Capote, together, we are six with three children. We have received help from some in each town as we have passed. And we have been treated badly by many people and we have had some ugly times like when we were dropped at night at the top of the mountain pass, pleno paramo, and we were hungry and cold and woke with ice on our bags. Many had offered to take us to Cúcuta and then they do not follow through. We thank each and everyone that has helped us.

I wondered about the other daughter, the one off in the distance. In the middle of the days walking, in the middle of all of this, why was she out there? Did her father send her to be alone to think about her behavior? Was she impatient and angry with her mother? Did she complain of the load she carried? Had she had a moment of tears when everyone needed to be strong now just two days from the border? Or, was she just up ahead when they had to stop and do the repair and to save on effort and energy she was just quietly waiting.

when

The father eventually stood, finished with attaching the harness to the bag. The daughter with our story book looked up and continued with an urgency, as if, writing something she herself, rather than the family, wanted to make sure was said and heard.

También algunos policías nos maltrataron, una vez, la gente del pueblo no nos quieran y nos sacaron a tiros, la policía no ayudo en nada solo nos dijeron ‘sigan su camino’. Que lo veo injusto porque entre nosotros hay niños. Luego nos tratan mal, nos sacan de los pueblos y nos dejan en montañas haciendonos creer que nos llevarán a Cúcuta, nos dejan en montes que no sabemos donde quedan, sin importarles que somos seres humanos.

Att: familia Figueredo Capote

And there were some police that treated us wrongly, one time we were in a place where the town’s people didn’t want us, they chased us out throwing rocks at us, the police didn’t help, didn’t do anything other than say, ‘go, continue on your road,’ It was not right, it was unjust, we were a family with children. It happened again and again, people were hostile when they spoke to us, they took us from towns and left us in the mountains letting us think they were taking us to Cúcuta, left in mountains where we had no idea where we were, it didn’t matter — that we were human beings.

Regards: the family Figueredo Capote

After inspecting each bag, the father tucked the wire and pliers into the last one and nodded to his daughter. She finished the last line and they packed up. I gave her a card for TodoSomos and asked her to write to us, to let us know what happens ‘….. that it was important for the world to hear.’ I wasn’t so sure the world was in any place to listen.

I thought about the stories we hear on this side of the border about what was up ahead for them — military and police in Venezuela treating the returnees like traitors, harsh words, harsh treatment, two weeks of garrisoned quarantine with little food and only an hour of running water each day.

I wanted to take a picture, the family, the bags, the carts ….. I didn’t, as it seemed to me it would have robbed them of what little they had left – pride, family, anonymity in a moment close to despair. They seemed like a really good family — the kind I wanted as a child, and the kind I hope for my patients.

He didn’t ask for anything. They didn’t wave.